Trading Places: How the U.S. Became a Nation of Importers

Key Takeaways

Free trade has helped shape the US economy, offering consumers lower prices and greater access to goods while fostering global political alliances.

Of late, policymakers have become more focused on the long-term costs of globalization, including rising trade deficits and declining domestic manufacturing.

Trade policy in the US and elsewhere is now evolving, with renewed emphasis on onshoring, tariffs, and renegotiated trade deals to strengthen supply chains and support American industry.

For decades, US policy prioritized free trade as a way of cementing political alliances and allowing consumers and businesses alike to access cheap goods. With that, for nearly 100 years, policymakers sought to encourage trade through lower tariffs and multilateral trade agreements. With the rise in trade came many benefits: lower-priced goods, a wider variety of goods and services, and a fast-growing economy.

But there were also drawbacks: a widening trade deficit, less control over our supply chains and declining manufacturing jobs. Over the last few years, there has been increasing focus on some of the drawbacks of global trade. With that change in focus also comes a sharp shift in policies that have both economic and political ramifications. Here we examine some of the history of trade in the US and what to expect going forward.

Trade Deficit: How Did We Get Here?

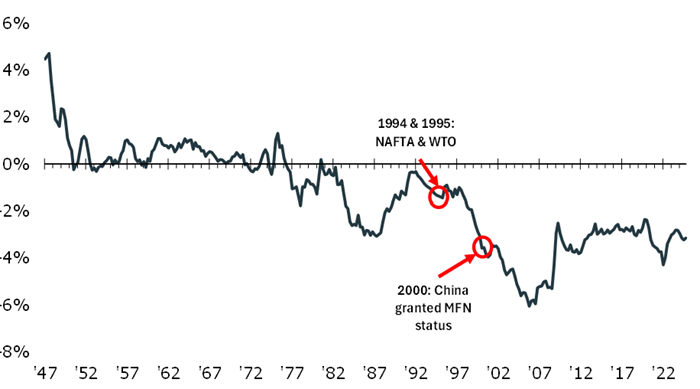

For most of the 20th century, the United States consistently ran a trade surplus – exporting more than it imported. Following World War II, when many countries around the world were rebuilding from the devastation the war had wrought, the US leveraged a strong manufacturing base to provide the world with the goods needed to rebuild. This began to change in the 1970s as other countries increased the competitiveness of their exports and economic shocks such as the oil crises of the 1970s impacted global trade.

The 1990s marked a further shift in trade policy with the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO)—agreements which aimed to increase trade and reduce trade barriers to expand access to cheaper goods. US companies shifted manufacturing to these newly available markets, such as China, which utilized their lower cost of capital and cheaper labor to become global manufacturing centers.

With these various shifts, the US has imported more goods and services than it has exported.

United States Trade Surplus / Deficit, 1947 – 2024 (% of GDP)

Source: Kestra Investment Management with data from FRED. Data from 1929-2024

Current State of Trade

With this multi-decade trend of globalization, the US economy has become deeply entwined with other countries. Today, the US’s top exports are energy and autos, while our top imports are also cars, car parts, energy, and electronic equipment. The fact that cars and car parts show up as our largest imports and exports demonstrates the complexity of trade and manufacturing – a finished good can often include pieces that cross multiple borders, or even the same border multiple times. The countries that we import the most from also tend to be the ones to which we export the most, including the European Union, Canada and Mexico. China is a notable exception where we import far more than we export.

Imports and Exports (Goods and Services) by Largest US Trading Partners ($m’s)

Source: Kestra Investment Management with data from the Office of Trade & Economic Analysis, Industry & Analysis, International Trade Administration of US Department of Commerce, and US Census Bureau. Data as of February 20225 with 2024 annual data.

What’s Next?

For decades policymakers were willing to accept widening trade deficits because of the perceived benefits: lower prices for businesses and consumers alike plus close political relationships with our largest trading partners. But these policies were not without their costs, namely the reduction of manufacturing in the US and the related jobs. With a greater focus on the costs of free trade, policymakers are changing tack.

Onshoring

COVID-19 and subsequent supply chain disruptions highlighted vulnerabilities in key industries, such as computer chips and pharmaceuticals. Policymakers and corporations are now prioritizing domestic manufacturing in these sectors.

Tariffs

The current administration has advocated for using tariffs to encourage more manufacturing at home, by making foreign-made goods more expensive and giving US-based companies incentive to build capacity locally.

Trade Deals

Finally, the administration has placed particular emphasis on re-negotiating existing trade deals, shifting from multi-lateral agreements such as the WTO and NAFTA to bilateral ones.

Why it Matters to You

After decades of prioritizing free trade, the US policymakers are focused on strengthening domestic industries and reducing reliance on foreign production. While trade has brought lower prices and stronger global ties, it has also contributed to job losses in certain industries and revealed vulnerabilities in key supply chains.

Policies like onshoring, tariffs, and reworked trade deals aim to rebalance the benefits and costs of globalization. Whether these efforts will successfully strengthen the US economy without sacrificing the gains of globalization remains to be seen—yet it seems clear that the era of unquestioned free trade is giving way to a more cautious approach towards economic policy.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author and may not necessarily reflect those held by Kestra Advisor Services Holdings C, Inc., d/b/a Kestra Holdings, and its subsidiaries, including, but not limited to, Kestra Advisory Services, LLC, Kestra Investment Services, LLC, and Bluespring Wealth Partners, LLC. The material is for informational purposes only. It represents an assessment of the market environment at a specific point in time and is not intended to be a forecast of future events, or a guarantee of future results. It is not guaranteed by any entity for accuracy, does not purport to be complete and is not intended to be used as a primary basis for investment decisions. It should also not be construed as advice meeting the particular investment needs of any investor. Neither the information presented nor any opinion expressed constitutes a solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security. This material was created to provide accurate and reliable information on the subjects covered but should not be regarded as a complete analysis of these subjects. It is not intended to provide specific legal, tax or other professional advice. The services of an appropriate professional should be sought regarding your individual situation. Kestra Advisor Services Holdings C, Inc., d/b/a Kestra Holdings, and its subsidiaries, including, but not limited to, Kestra Advisory Services, LLC, Kestra Investment Services, LLC, and Bluespring Wealth Partners, LLC. Does not offer tax or legal advice.